The Thames may appear to flow naturally from its source in Gloucestershire to the sea at the Thames Estuary, but much of what we take for granted on the river is the result of centuries of careful engineering. Locks and weirs are the quiet workhorses of the Thames, ensuring that water levels remain safe, floods are controlled, and boats can continue to pass up and down the river.

For commuters in London, they may seem like something that happens further upstream, out of sight. Yet without these structures, the river through the capital would look and behave very differently. For leisure boaters, anglers, and riverside communities, locks and weirs shape almost every experience on the Thames.

This article explores how locks and weirs function, why they matter, and what boaters need to know when passing through them. It also looks back at how the river was managed before these structures existed, and why they remain essential today.

- Introduction to The Tidal and Non-Tidal Thames

- A Short History of Thames River Management

- What Locks and Weirs Actually Do

- How Locks and Weirs Affect Boaters

- How to Use a Lock in Practice

- Why Locks and Weirs Matter Beyond Boating

- Building Confidence Around Locks

- The Future of Thames Locks and Weirs

- The Working River

- Download the Thames Commuter App

Introduction to The Tidal and Non-Tidal Thames

The River Thames is essentially two rivers in one: a controlled freshwater system upstream (towards the source) and a tidal estuary downstream (towards the North Sea). The change happens at Teddington Lock, the last lock on the river from the source and the boundary between managed flow and natural tide.

Upstream of Teddington lies the non-tidal Thames, stretching more than 140 miles to Lechlade in Gloucestershire. Here, locks and weirs control the depth and flow of water for navigation, flood management, and ecology.

Downstream of Teddington, the tidal Thames takes over. This lower stretch rises and falls twice daily with the tide, carrying a mix of freshwater and saltwater toward the North Sea. It’s managed not by locks, but by tidal gates and defences such as the Thames Barrier, which protect the city from surges.

Together, these two systems work in balance. The controlled flow from upstream keeps the tidal Thames stable by preventing sudden surges of water during heavy rain, and maintaining oxygen and depth during dry spells. Without this upstream regulation, London’s stretch of river would experience greater extremes, and the Thames Barrier would face far higher strain holding back the tide.

A Short History of Thames River Management

The Thames has been shaped by human hands for centuries. Before the introduction of modern pound locks, the river was dotted with “flash locks” and fish weirs, crude barriers that diverted water for mills and fisheries. These often blocked navigation entirely, forcing bargemen to struggle upstream against unpredictable currents or wait until gates were opened in a sudden rush of water. It was a dangerous and inefficient system, and disputes between boatmen and millers were common.

The first proper pound locks began to appear on the Thames in the 17th and 18th centuries, transforming navigation. These new structures allowed boats to be raised or lowered steadily without the violent surges of flash locks. As London expanded and river trade grew, locks and weirs became indispensable, making the upper Thames a reliable artery for goods and later a playground for leisure.

Today, the Environment Agency manages most of the Thames’s locks and weirs, blending historic infrastructure with modern technology. Many structures still retain their traditional character, with manual gates and oak timbers, but they are now supported by automated sluices, telemetry, and remote monitoring. This balance of old and new reflects the long history of adapting the Thames to meet the needs of each generation.

What Locks and Weirs Actually Do

Locks and weirs often sit side by side, working together to keep the Thames navigable and safe. They perform different but complementary roles, balancing navigation with flood control.

Locks: Step Ladders for Boats

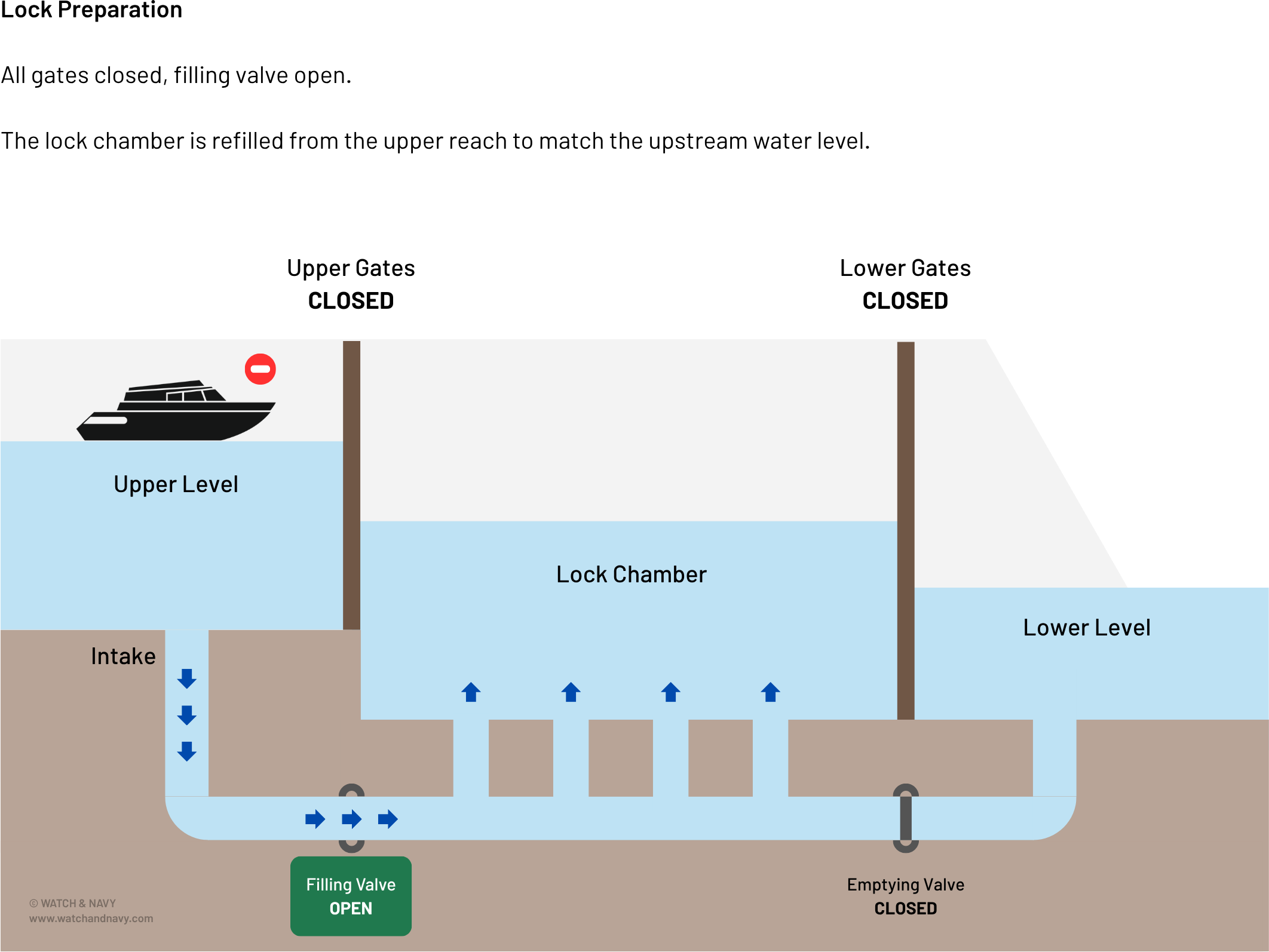

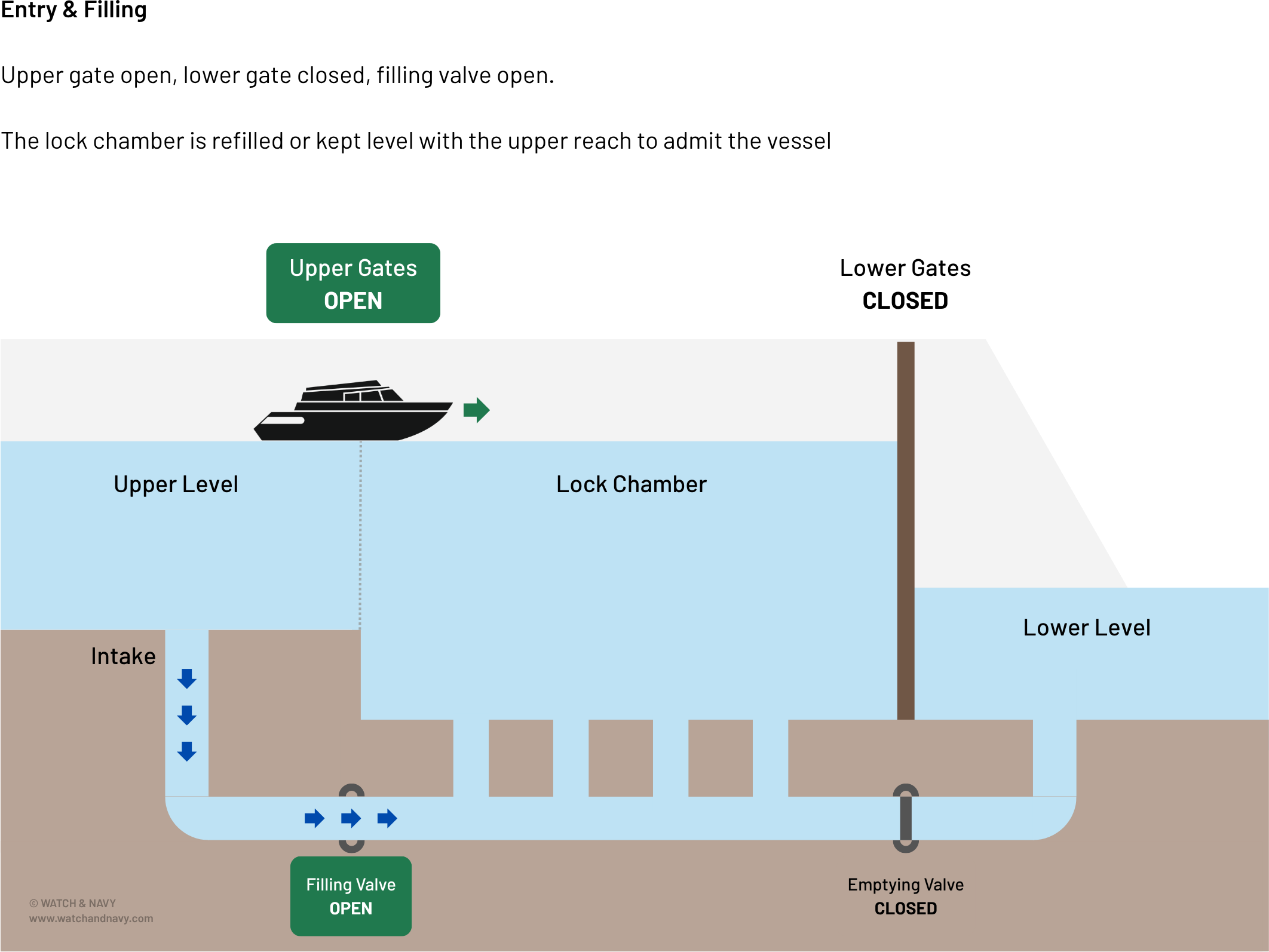

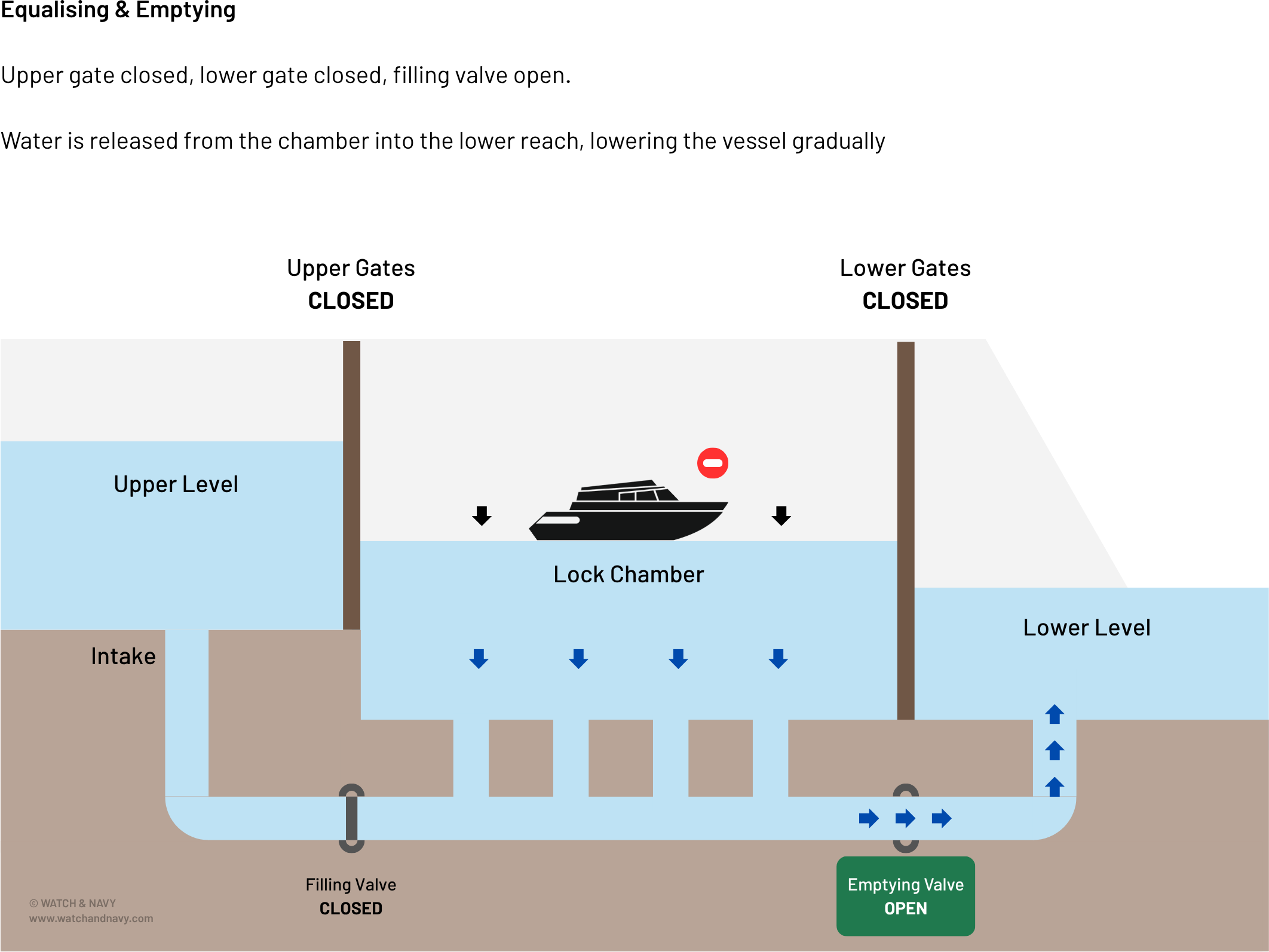

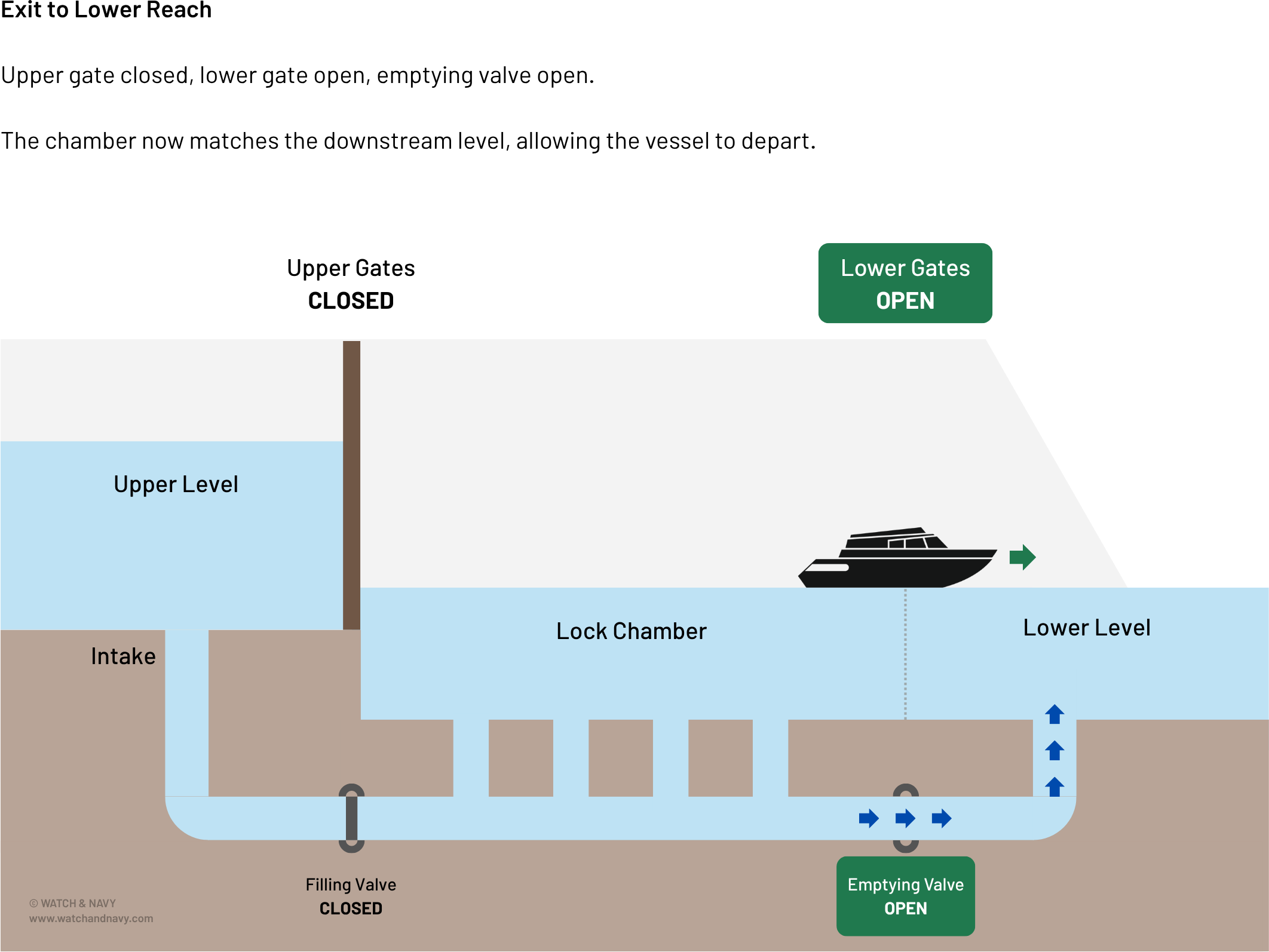

Locks act like water elevators. They raise and lower boats between stretches of the river where the water level is different. Closing the gates and letting water in or out lifts a boat upstream or lowers it downstream.

Without locks, large sections of the upper Thames would be too shallow in summer and too turbulent in winter for consistent navigation. For commercial barges in the past and leisure craft today, locks remain essential.

Weirs: Controlling the River’s Flow

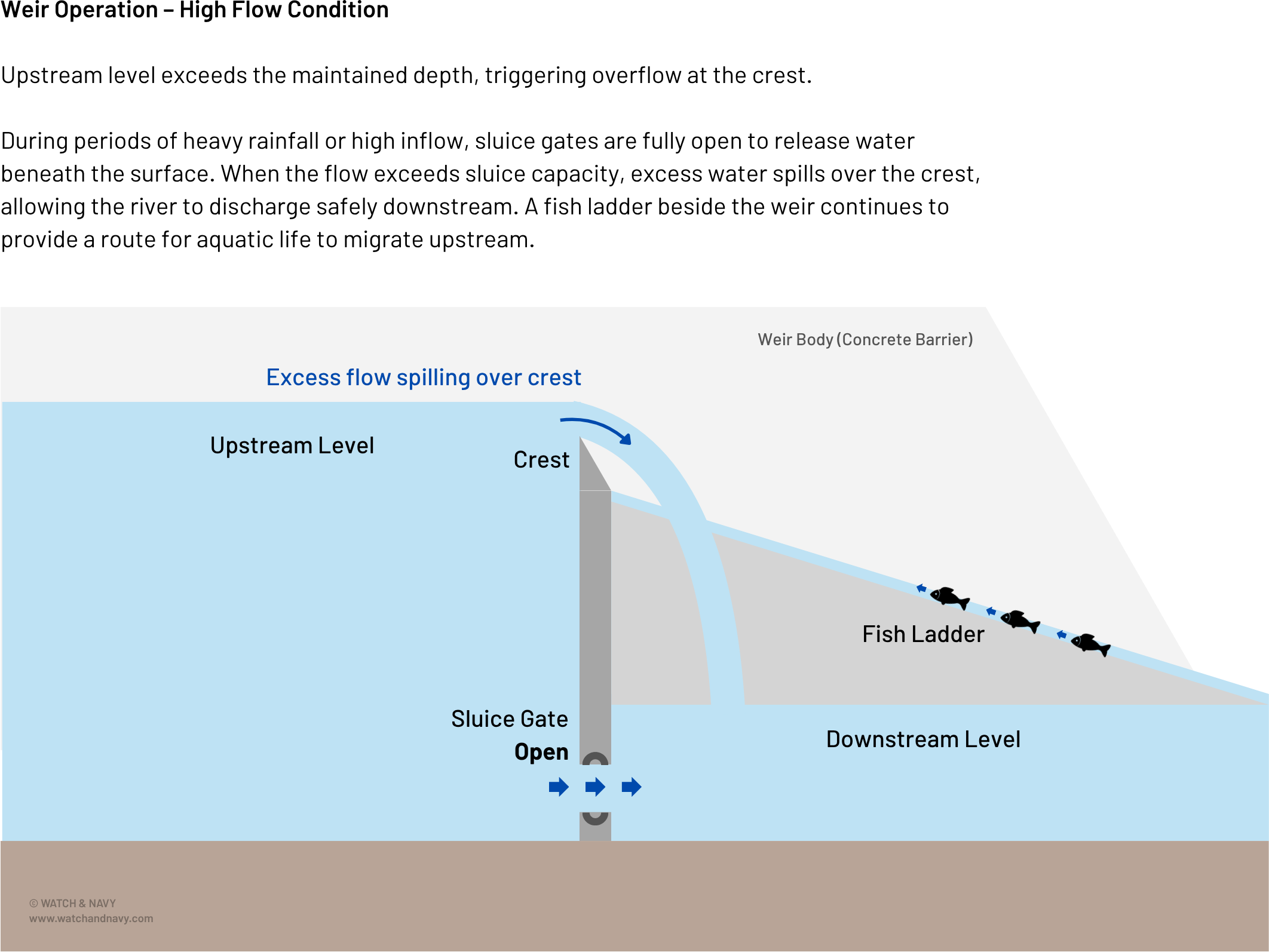

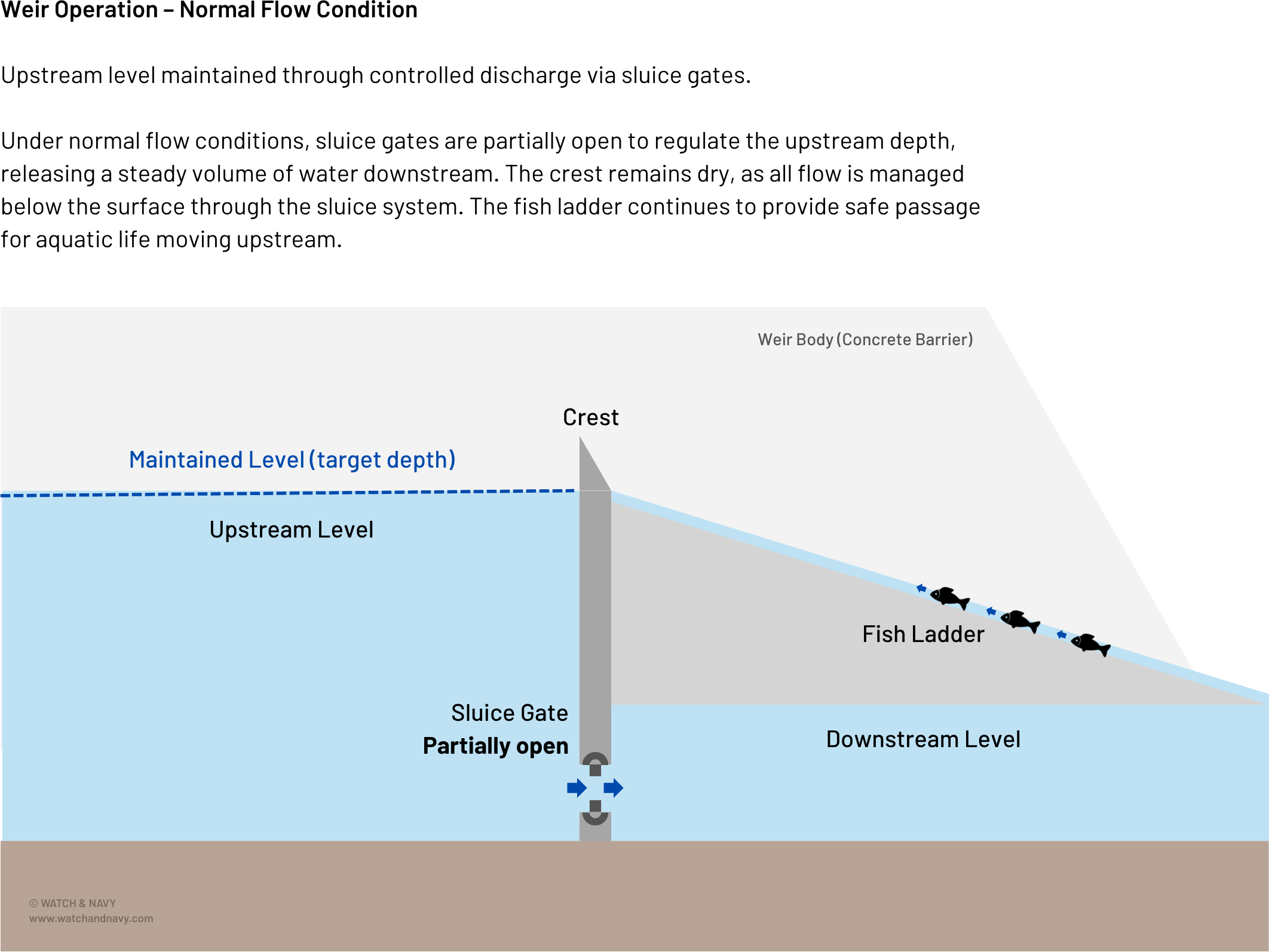

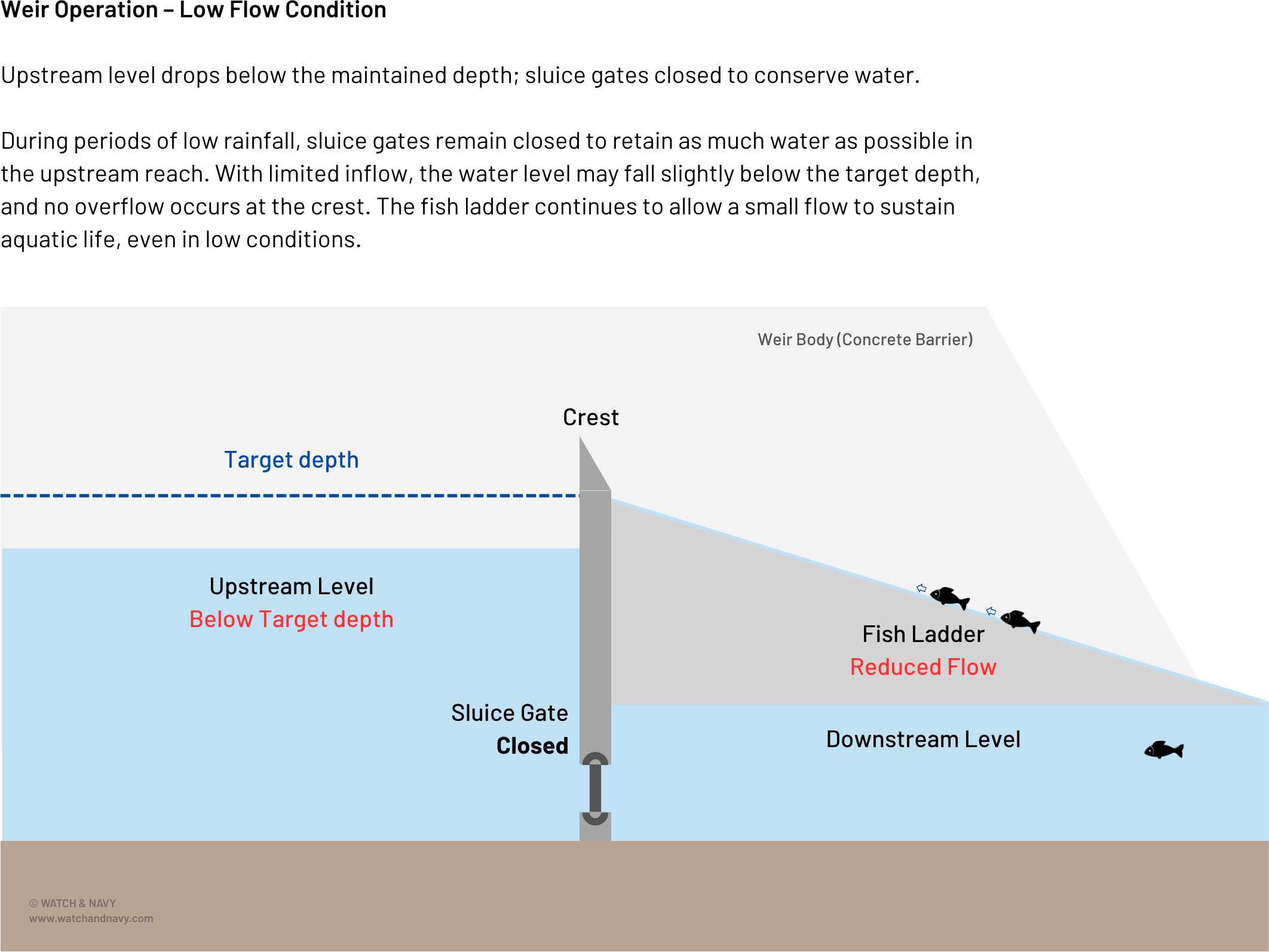

A Weir is a structure that stretches across the river, controlling how much water passes through. Sluice gates (steel panels that raise or lower to control flow) manage the volume of water released downstream. Adjusting these gates keeps the upstream level steady. This helps in three key ways:

- Flood control: Excess water after heavy rain can be released gradually.

- Navigation: Maintaining a minimum depth for boats, even during dry spells.

- Ecology: Weirs oxygenate the water and, with modern fish passes, allow wildlife to thrive.

Why Locks and Weirs Work Together

A lock on its own cannot function if water levels are not regulated, and a weir without a lock would block navigation entirely. Together, they form a system: the weir holds the water back, and the lock provides the doorway for boats to move through.

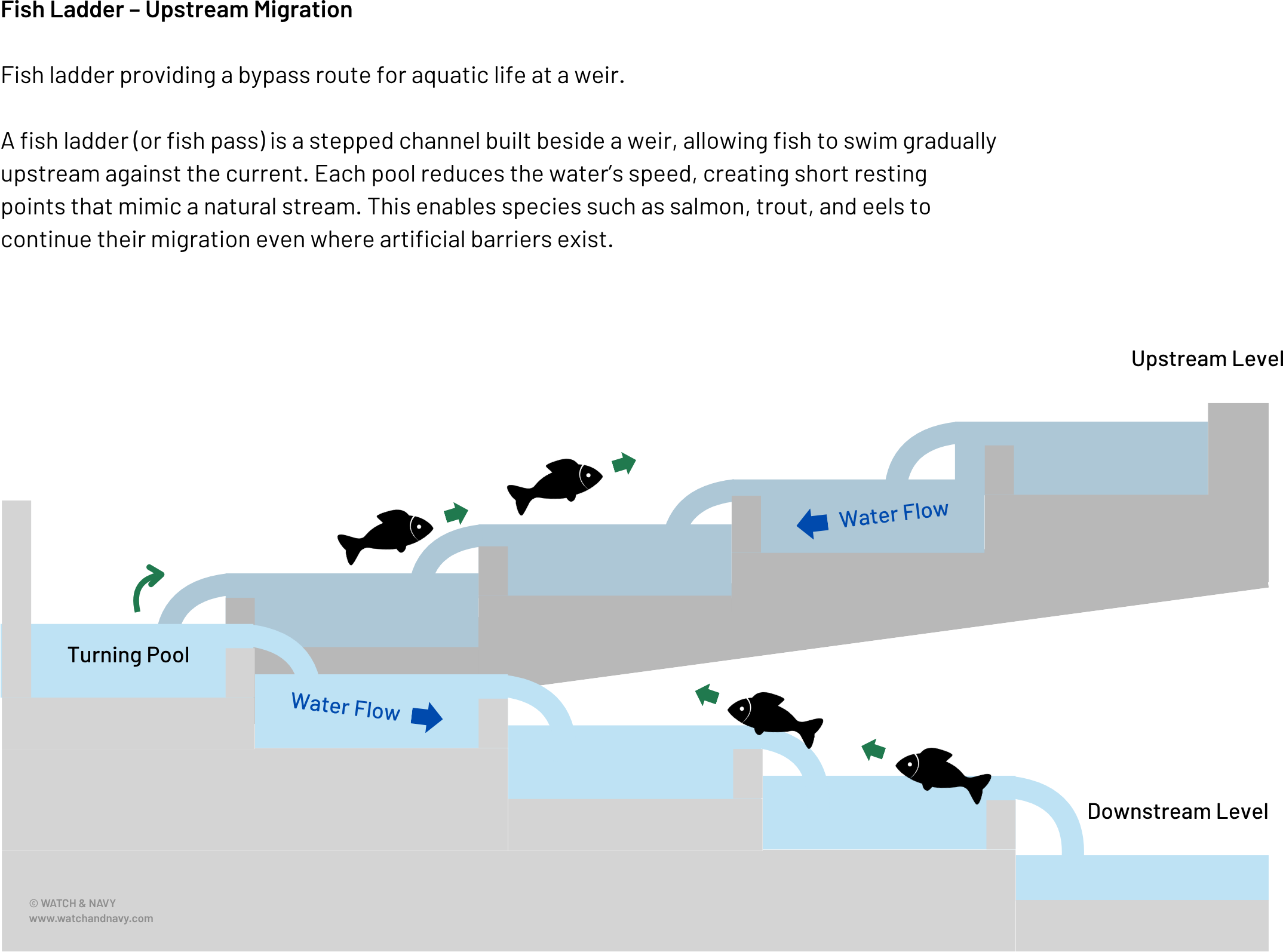

Fish Ladders: Keeping the River Alive

For centuries, weirs cut off fish from their natural migration routes. The addition of fish ladders in the modern era turned barriers into bridges; subtle but vital structures that allow the river’s ecology to coexist with its engineering.

By reintroducing movement into calmer reaches, they improve oxygen levels and habitat diversity, supporting insects, plants, and other species that depend on a living current. This circulation helps sustain entire food webs within the river, ensuring that all managed stretches maintain a healthy natural ecosystem.

How Locks and Weirs Affect Boaters

For boaters on the Thames, locks and weirs are more than pieces of infrastructure, they directly influence the rhythm and safety of every journey.

Closures and Maintenance

Locks are occasionally closed for scheduled works or unexpected repairs. The Environment Agency usually publishes these in advance, but for those travelling long distances, it can mean reshuffling plans or facing diversions. Weirs may also be adjusted to manage floods, temporarily altering local conditions.

Delays and Queues

On summer weekends or during regattas, popular locks can see queues forming. Boats often need to wait their turn, sometimes sharing chambers with others. Patience is part of the process, and experienced boaters treat it as a social moment on the river.

Safety Near Weirs

Weirs create strong currents and turbulence that can catch out inexperienced boaters. Red and green lights, positioned near locks and sluices, indicate whether it is safe to proceed. Ignoring signals or drifting too close to a weir can be dangerous, which is why awareness is vital.

Seasonal Conditions

Heavy rainfall upstream means weirs may release large volumes of water, creating fast flows. During dry spells, they conserve water to keep levels navigable. In both cases, boaters feel the effect in stronger currents or restricted passages.

Reminders for boaters:

- Always check navigation notices before setting out.

- Approach weirs with caution; follow light signals.

- Expect queues at popular locks in summer.

How to Use a Lock in Practice

For newcomers, the first lock can be intimidating. Yet the process is straightforward once you understand the signals, etiquette, and common pitfalls.

Signals and Approach

- Red light: Do not enter– lock is closed.

- Amber light: Prepare to enter, or wait for instructions.

- Green light: Safe to proceed.

Always slow your approach. Hold position steadily until you are invited in. Strong currents can make this more difficult, so allow extra time and space.

Etiquette Inside the Lock

Locks are communal spaces, and courtesy makes the process smoother:

- Share chambers with other boats where possible.

- Communicate clearly with lock keepers and fellow boaters.

- Secure your boat with ropes fore and aft.

- Switch off engines once secured to reduce fumes.

Common Mistakes

Newcomers often repeat the same errors, which can be avoided with care:

- Forgetting to tie off lines securely.

- Trying to hold ropes by hand rather than fastening them.

- Standing on the edge of wet lock walls.

- Leaving engines running in enclosed spaces.

Why Locks and Weirs Matter Beyond Boating

Although they are most visible to boaters, locks and weirs serve a much wider purpose. Flood control is perhaps the most crucial. By regulating the river’s flow, these structures protect thousands of homes and businesses along the Thames from the damage of sudden surges after heavy rain. They also ensure that London’s water supply can be safely drawn from the river, maintaining steady levels that feed reservoirs and treatment plants.

Locks and weirs play a role in ecology as well. Modern weirs are often fitted with fish passes that allow species such as salmon and eels to migrate upstream, reconnecting habitats that were once blocked. The steadying of water levels also benefits wetland areas and supports biodiversity along the banks.

For many people, the cultural and leisure value is equally important. Locks in particular have become landmarks, drawing walkers, cyclists, and holidaymakers. On a summer afternoon, a lock-side can be as much a social hub as a working piece of infrastructure, offering a glimpse of the engineering that keeps the river alive. Without them, the Thames would be less safe, less accessible, and less vibrant.

Building Confidence Around Locks

For newcomers, using a lock can seem daunting: heavy gates, rushing water, and the need to work alongside other crews. But in practice, locks are designed to be safe and straightforward, especially with lock keepers on hand to guide the process.

Confidence comes through observation and repetition. Watching other boats use a lock is often the best introduction. Noting how ropes are secured, when engines are switched off, and how communication is handled gives first-time boaters a clear sense of what to expect. Many lock keepers are happy to explain procedures and answer questions, making locks not only functional but also educational spaces on the river.

Training courses also offer opportunities for those wanting extra reassurance. The Environment Agency and boating organisations guide safe lock use, etiquette, and river navigation. Over time, the routine becomes second nature, and the lock stops being an obstacle; it becomes part of the journey itself, a place where boaters pause, interact, and enjoy the slower rhythm of the Thames.

The Future of Thames Locks and Weirs

Like the river itself, the management of the Thames is constantly evolving. Traditional lock-keeping, with its oak beams and manual gates, is gradually being supplemented by modern systems. Remote monitoring, automated sluices, and digital sensors are already in use at several sites, giving the Environment Agency more precise control over water levels and flood risks.

There is also growing emphasis on sustainability. Many weirs now incorporate fish passes to reconnect habitats and support species that had once vanished from the river. Some lock sites have trialled small-scale hydroelectric turbines, using the steady flow of water to generate renewable energy for local communities.

For boaters and riverside visitors, these changes may not always be visible, but they represent a long-term shift in how the Thames is managed. The challenge is to balance tradition and heritage with innovation. Locks and weirs remain historic landmarks, but they are also part of a living system that must adapt to climate change, heavier rainfall, and the growing demands of those who rely on the river.

The Working River

Locks and weirs are the hidden machinery that keep the Thames working. Without them, the river would be unpredictable, prone to floods in wet seasons and unnavigable in dry ones. They regulate the flow of water, make navigation possible, protect riverside communities, and preserve habitats that depend on a stable river system.

For boaters, they are part of the rhythm of travelling upstream or downstream. For walkers and visitors, they are points of fascination and beauty, places where the engineering of the river is laid bare. From the tidal gateway at Teddington to the quieter reaches above Oxford, each lock and weir is a reminder that the Thames is both natural and engineered, a living river shaped by centuries of human effort.

Next time you pass a lock, whether by boat, bicycle, or on foot, pause to consider the role it plays. Far from being a barrier, it is the reason the Thames remains open, safe, and vibrant. In understanding these structures, we come closer to understanding the river itself.

Download the Thames Commuter App

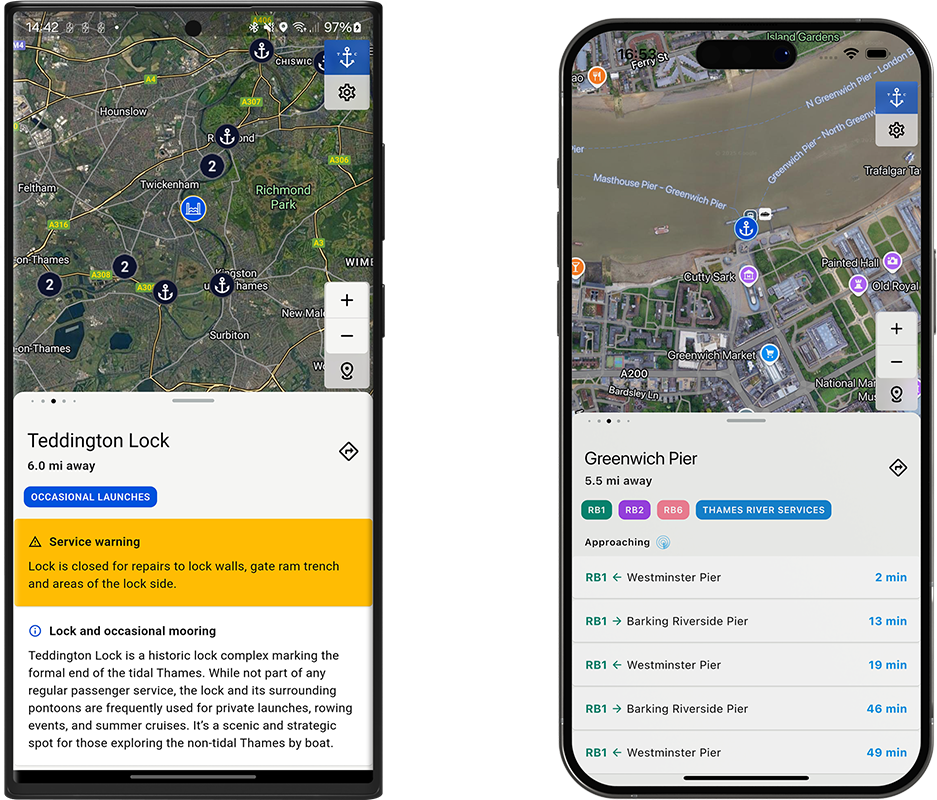

For those keen to explore the river in detail, the Thames Commuter app is now expanding coverage inland. Alongside timetables and real-time arrivals for London piers, it now includes information on all 45 locks and weirs further upstream, helping boaters and river watchers stay up to date with current conditions.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.